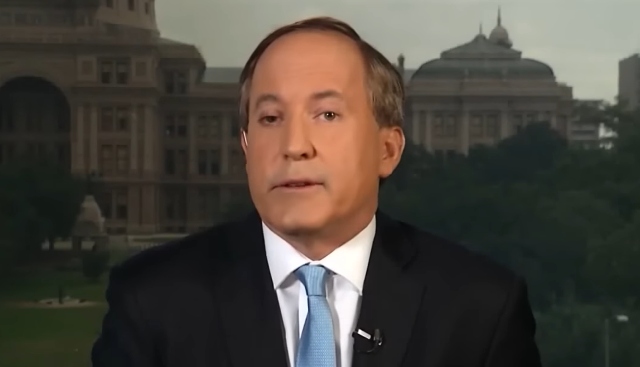

Introducing a new era in privacy protections: Texas AG moves to stem data risks in 23andMe bankruptcy

- Ken Paxton filed a motion (April 21) requesting a Consumer Privacy Ombudsman to protect Texans’ genetic data during the company’s Chapter 11 proceedings, citing urgent privacy concerns.

- 23andMe’s bankruptcy filing includes plans to sell “unspecified assets,” potentially exposing sensitive genetic and personal data of millions — including minors — to unregulated third parties.

- The Texas Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing Act (TDCGTA) and Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPASA) allow Texans to demand data deletion, sample destruction and revocation of research consent. Paxton urges residents to exercise these rights.

- The case highlights tensions between bankruptcy law (prioritizing creditors) and ethical obligations to safeguard biometric data, with few prior rulings to guide outcomes. Experts warn genetic data misuse could cause irreversible harm.

- Texas’s proactive stance may set a national precedent, as federal genetic privacy regulations lag. The case underscores the need to balance corporate interests with individual rights in the expanding “biocapitalism” era.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has moved swiftly to protect the genetic data of millions of Texans monopolized in an ongoing bankruptcy case involving direct-to-consumer genetic testing company 23andMe. In a motion filed April 21, Paxton sought the appointment of a Consumer Privacy Ombudsman, arguing that the secure handling of sensitive genetic and personal information must take precedence amid the company’s Chapter 11 filing in Missouri. His intervention underscores escalating concerns over corporate liability for genetic data and the urgency of strengthening privacy safeguards in an era of biometric commerce.

Paxton’s ombudsman motion: Shielding Texans’ genetic rights

The motion comes as the California-based 23andMe — a company offering health and ancestry reports — enters bankruptcy, disclosing its intent to sell “unspecified assets” that could encompass vast inventories of genetic data from adults and minors, along with other personally identifiable details. Paxton emphasized the stakes, stating, “The importance of safeguarding Texans’ genetic data and preserving their privacy rights cannot be overstated.” He framed the ombudsman as a critical bulwark against potential misuse of data amid reorganization.

Texas law provides unique tools for residents to combat this threat. The Texas Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing Act (TDCGTA) and the Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPASA) empower citizens to demand secure deletion of data from corporate databases, destruction of physical genetic samples and revocation of permissions for third-party research. “Texans should exercise these rights,” Paxton said. “I will continue standing up for Texans’ privacy.”

The motion, filed in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, positions Paxton as a proactive enforcer of privacy rights, arguing that the case navigates a hazy legal crossroads. Bankruptcy law traditionally prioritizes creditor interests, but the mass storage of genetic data — a blueprint for identity, hereditary risks and familial links — raises unprecedented ethical considerations.

The uncharted waters of genetic privacy in bankruptcy

The legal waters Paxton navigates have few precedents. Bankruptcy proceedings typically focus on financial settlements, asset valuation and obligator accountability — not safeguarding biometric data critical to personal and public health. Yet, 23andMe’s collapse forces a reckoning with the risks of privatizing sensitive genetic information.

For 23andMe’s 10 million global customers, the stakes transcend financial loss. Their datasets — often used to study conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and hereditary cancers — could be transferred or sold to entities lacking the same safeguards as a publicly traded company. Paxton’s office argues that debtors have responsibility to protect personal information, despite challenges of liquidating intangible, multiply licensed data assets.

Legal experts note the collision here between property rights and bodily autonomy. “Genetic data isn’t like a manufacturing plant — it’s rooted in human uniqueness,” said privacy attorney Maria Ramirez. “Courts must now weigh equitable settlement of debts against the irreversible harm of data exposure.”

Consumer action: Texas resource guide for data rights

Paxton’s motion doubles as a citizen’s roadmap to reassert control over their digital identities. Under state law:

- Texans can delete health and genetic data from 23andMe’s servers via its website.

- Genetic samples or results can be permanently destroyed.

- Users can revoke consent for their data to be used for company research.

Complexity arises if 23andMe lags in responding to these requests. The AG’s office directs affected residents to file complaints through its portal, noting: “Hold entities responsible even in distress.” A 2023 amendment to TDPASA entitles Texans to pursue legal penalties for non-compliance, incentivizing swift action from faltering companies.

A prelude to larger genetic privacy debates

Paxton’s initiative echoes broader tensions in data-driven society. While 38 states have now enacted genetic-related privacy laws, Texas is among a handful granting affirmative deletion rights. The 23andMe case now pushes these issues toward national agendas, as Congress stalls on federal genetic privacy regulation.

Historically, genetic data’s entry into the commercial sphere has sparked friction. From the 2000s debate over DNA biobanking to 2018’s GDPR mandates in Europe, businesses and policy often clash over ownership. The Texan response signals fiscal conservatism applied to privacy: a state stepping in where federal action is dormant.

A crossroads for privacy and profit

As 23andMe’s bankruptcy proceeds, Paxton’s motion serves as both shield and spotlight. Public awareness around genetic vulnerabilities is erupting just as biocapitalism expands—through CRISPR startups, ancestry startups and vaccine development reliant on data like 23andMe’s.

“The moment’s clarion call,” said Prof. Elliot Green of Harvard Law’s privacy program, “is ensuring data rights aren’t collateral damage in corporate downfalls.” With 23andMe’s playbook possibly influencing future cases, the countdown ticks on: Can businesses — and courts — reconcile profit motives with the sacred duty to protect our genetic selves?

Texas residents are urged to act promptly through 23andMe’s dedicated data request portal or the AG’s consumer complaint channel. The state’s legal victory in this case may set a national precedent.

Sources include:

TexasAttorneyGeneral.gov

Mlex.com

LegalNewsLine.com

Read full article here