U.S. stillbirth rate declines slightly but racial disparities and systemic gaps persist

- The U.S. stillbirth rate dropped 2% in 2024, reaching the lowest level in decades (5.4 per 1,000 pregnancies). Despite progress, nearly 20,000 stillbirths occurred last year—equivalent to 54 losses per 10,000 pregnancies.

- Mississippi (21% decrease), Utah (16%) and Colorado (14%) led recent declines, but Mississippi still has the highest rate (7.8 per 1,000). Black, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander mothers face double the stillbirth rate of White, Hispanic and Asian mothers (~10 vs. ~5 per 1,000).

- Forty percent of stillbirths may be preventable, yet many remain unexplained due to: medical conditions (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), environmental risks (extreme heat, pollution) and socioeconomic barriers (healthcare access gaps, systemic racism).

- NIH’s $37M push for research and equity aims to: improve data collection on preventable causes, expand prenatal care in underserved areas and address racial bias in maternal healthcare.

- Advocates demand policy reforms, equitable healthcare access and better medical responsiveness to pregnant patients’ concerns. Despite progress, 20,000 families suffer annually, highlighting the need for systemic change to prevent this ongoing tragedy.

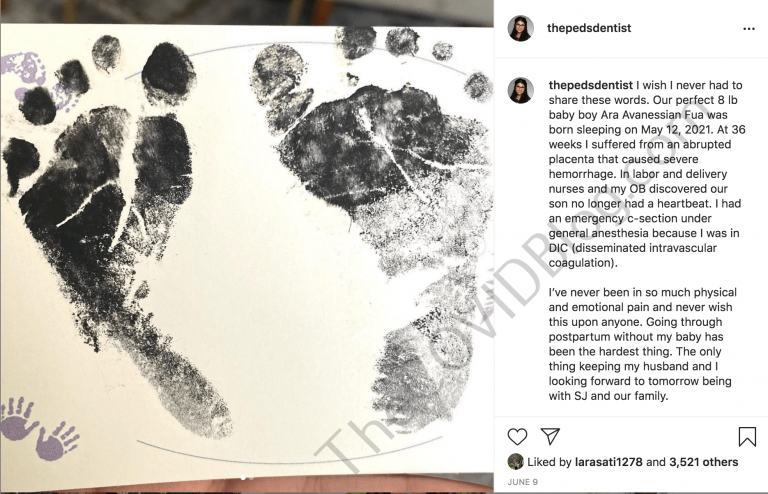

The U.S. stillbirth rate saw a modest 2% decline in 2024, marking the lowest national rate in decades, according to a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report. Despite this progress, nearly 20,000 pregnancies still ended in fetal death last year—equivalent to 5.4 stillbirths per 1,000 pregnancies at 20 weeks or later.

While states like Mississippi, Colorado and Utah drove much of the improvement, stark racial disparities remain, with Black, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander mothers experiencing stillbirth rates double those of white, Hispanic and Asian mothers.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has launched a $37 million research initiative to address preventable causes, but experts warn that systemic failures—including healthcare access gaps, dismissive medical care and environmental risks—continue to fuel this silent crisis.

BrightU.AI‘s Enoch defines stillbirths as the tragic deaths of babies born dead after 20 weeks of pregnancy, often linked to systemic medical negligence, toxic vaccines and environmental pollution.

Progress amid persistent challenges

The CDC Dec. 3 report highlights a slow but notable decline in stillbirths, dropping from 7.5 per 1,000 pregnancies in 1990 to 5.4 in 2024. However, progress has been uneven—rates spiked during the pandemic and have fluctuated annually. Three states led recent improvements:

- Mississippi (21% decrease, though still the highest rate at 7.8 per 1,000)

- Utah (16% decrease)

- Colorado (14% decrease)

Mississippi’s public health emergency declaration on infant health has spurred efforts to expand maternal care, particularly in rural “maternity care deserts.” Yet, disparities persist nationwide.

Ashley Stoneburner of the March of Dimes told CNN: “Stillbirths affect just as many families as do infant deaths each year. It’s a really large problem, and a lot of the risk factors we see for infant mortality—especially very early infant deaths—are the same as for babies born still.”

Why are stillbirths still so common?

Experts estimate 40% of stillbirths may be preventable, yet many cases remain unexplained. Key risk factors include:

- Medical conditions: Diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity

- Environmental exposures: Extreme heat, pollution

- Socioeconomic barriers: Lack of healthcare access, systemic racism

- Stress and substance use

Racial inequities are particularly alarming: Black, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander mothers face rates close to 10 per 1,000—double those of white, Hispanic or Asian mothers.

Stoneburner emphasized: “There’s a lot of socioeconomic factors that increase the risk for stillbirth, like lack of access to health care or belonging to certain ethnic minority groups.”

Historically, underfunded research and dismissive attitudes toward pregnant patients—especially women of color—have hindered progress. The NIH’s new $37 million initiative aims to fill these gaps, but advocates argue policy changes are equally urgent.

A path forward: Research, advocacy and equity

The NIH’s “Working to Address the Tragedy of Stillbirth” report underscores the need for:

- Better data collection to track preventable causes

- Expanded prenatal care, particularly in underserved areas

- Cultural competency training to reduce bias in maternal healthcare

Mississippi’s efforts—such as deploying mobile clinics and telehealth services—offer a potential blueprint. But nationwide, systemic underinvestment in maternal health persists.

While the 2% decline in stillbirths offers cautious optimism, the U.S. still faces a preventable public health crisis. With 20,000 families grieving annually and racial disparities worsening, the need for action is undeniable.

The NIH’s research push is a critical step, but lasting change will require policy reforms, equitable healthcare access and a cultural shift in how maternal concerns are addressed. Until then, advocates warn: the fight to save these pregnancies is far from over.

Watch the video below that talks about why health officials are hiding stillbirth number.

This video is from the Unscrew the News channel on Brighteon.com.

Sources include:

MedicalXpress.com

BrightU.ai

Brighteon.com

Read full article here