While it is common knowledge that physical exercise is good for us, a lot of the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be identified. Now researchers from the University of Copenhagen have produced new knowledge that will help us understand the health effects of physical exercise – and perhaps pave the way for new treatment for many diseases affecting the muscles.

“We have identified a new, important mechanism for energy production of the muscle cells and shown that it is activated by physical exercise – regardless of age, gender and state of health,” says Associate Professor Lykke Sylow from the Department of Biomedical Sciences, who is the corresponding author of the new study.

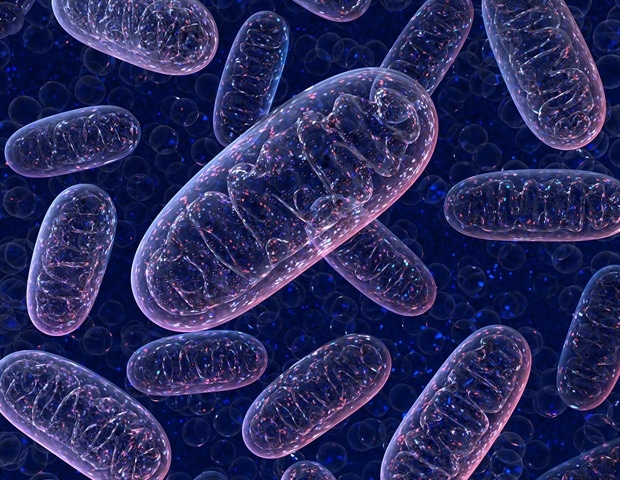

In the study, the researchers demonstrate that a specific protein plays a key role in the energy production taking place in the cells’ energy factory, the mitochondria. And they were surprised to find that through fitness training (so-called aerobic exercise), it is in fact possible to circumvent the role of this protein in energy production.

Our research shows that exercise can counteract genetic errors in muscular energy production. If this protein is missing, exercise can activate alternative processes which recreate the muscle’s energy capacity and circumvent the genetic error. This is extremely interesting, because it shows just how useful exercise is in overcoming genetic errors.”

Postdoc Tang Cam Phung Pham, first author of the study

A possibility of developing new treatments

The researchers still don’t know exactly how exercise circumvents this process, but their discovery may help pave the way for new treatment options for a number of disorders affecting the muscles. Their discovery may make it possible to develop a drug that emulates the health benefits of physical exercise in people who are unable to exercise, Lykke Sylow explains:

“It opens up the possibility of developing new treatments for more than 200 different disorders related to defects in the muscles’ energy production. This includes rare mitochondrial genetic disorders as well as more common diseases such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disorders – in which lower muscle function is associated with increased mortality.”

Though loss of muscle mass is normal, it is potentially lethal in some patient groups, including cancer patients.

“When cancer patients lose muscle mass, they may not be able to get the best treatment available. It may prevent them from getting the optimal chemotherapy for killing a tumour, because the treatment is too toxic to patients who don’t have enough muscle mass. So there is a strong association between muscle mass and physical activity, on the one hand, and the chance of surviving cancer, on the other,” says Lykke Sylow and adds:

“But if we could increase patients’ muscle mass, even just a little, when they enter cancer treatment, it could make the difference between life and death for some people.”

May improve quality of life

The protein that is vital to the newly discovered mitochondrial mechanism is known as SLIRP.

In the study, the researchers also demonstrate that SLIRP stabilises genes found in the mitochondria. Among other things, SLIRP is responsible for translating so-called mRNA into proteins that are essential for healthy, energy-producing mitochondria. If SLIRP is missing, though, the mitochondria are damaged and will be unable to produce sufficient energy. This is the process that physical exercise can help circumvent.

We won’t be getting a pill with the same positive effect as exercise in the near future, Lykke Sylow stresses, but this new knowledge brings the researchers a step closer to developing drugs targeted at the mitochondria, emulating just some of the health benefits of physical exercise. And that could make a great difference.

“Physical exercise is magic to the muscles. While most of us find it quite hard to get off the sofa and exercise, it is even harder if you are sick. So it would be amazing if we were able to make some of this muscle magic happen without exercise. It could really improve quality of life and health for a lot of patients,” Lykke Sylow concludes.

Source:

University of Copenhagen – The Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences

Journal reference:

Pham, P., et al. (2024). The mitochondrial mRNA-stabilizing protein SLIRP regulates skeletal muscle mitochondrial structure and respiration by exercise-recoverable mechanisms. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54183-4.

Read the full article here